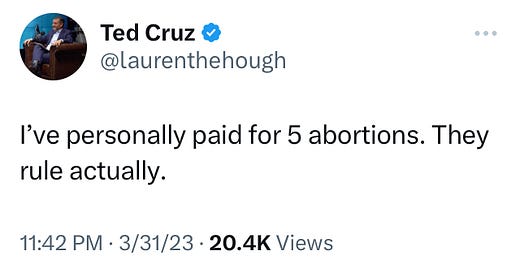

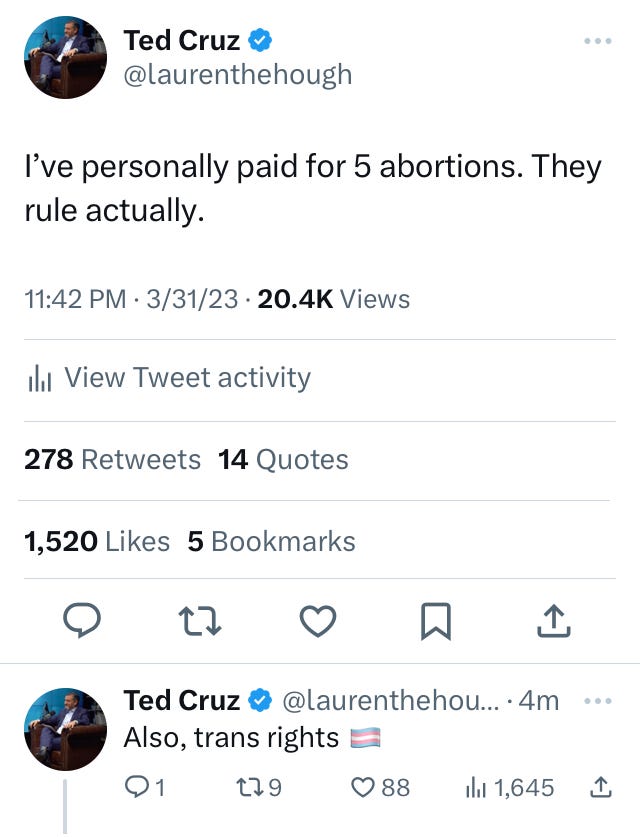

I should’ve done it long ago, but I’m a coward. I could’ve done it in better fashion. I could’ve used my checkmark to impersonate Ted Cruz and tweet eloquently on safer gun laws and protecting the rights of immigrants and trans people. But I’ve never been all that eloquent on twitter. I tweeted about my life, played around with friends when a current event became a joke-writing workshop. I talked about my dogs, Dolly Parton, shitty jobs, and my book.

It wasn’t all bad for a while. Twitter was a place I could connect to writers and people who create. I could get publishing advice, sell an essay about being a cable guy and working conditions in America, or an essay about needing to pee depending on how you read it.

When I sold that essay, I’d nearly given up on the idea of being a writer. I was working as a bouncer taking classes at Austin Community College, occasionally driving for Lyft. In my free time, I’d tweet. I’d tell bar stories and talk about my dog. I’d try to build what publishers call a platform. It did work. In no small part because of twitter, the cable guy essay went viral and I sold a book. I’d tweet about that too. Try to get people to pre-order the book. Preorders are crucial to book sales. They tell bookstores how many copies to buy. And they’re all counted in the first week of sales. If you’re an unknown author, like I was, you need those presales to have any chance of hitting the bestseller list.

You’re told a platform is critical to publishing, especially if you write non-fiction. Publishers want to know you have a built-in audience who will buy your book. No one really knows that that means or what works. Really. No one knows if Twitter or Instagram sell books, or whose books they sell. TikTok has landed some authors on lists. But for every success story, there are thousands of authors talking to the ether. Still, creators of all forms are encouraged, if not required to build and maintain an audience on social media. For writers, more often than not, that medium has been Twitter. Twitter was where we networked, built followings, sold work, and promoted our work, and the work of other creators.

What I didn’t realize is that I was developing an addiction. Maybe we never do know until it’s too late. I’d wake up in the morning and check twitter before I had coffee, before I took my dog out for a walk. I’d look at twitter during those walks. I’d scroll twitter while cooking, while eating, and I’d wake up in the middle of the night, to fucking check twitter. I couldn’t open my phone to check the weather without my thumb unconsciously hitting the twitter app, and before I knew it, the thunderstorm had passed.

But I told myself Twitter was a necessary evil. This was my first book. This was what I wanted, to be a writer. Because of the following list I’d curated, I mostly interacted with journalists, comedians, and fellow writers. During the lockdowns, maybe especially for those of us who were alone, Twitter felt like a way of connecting to other human beings. My dog was getting older and I talked about that too. I needed to tell someone. I needed people to see how beautiful he was. I needed someone to see how much it hurt to lose him. I needed a goddamn hug. What I had was twitter.

I’d forget too often that there’s a darker side of twitter—right wing twitter, yes, but also those who cannot feel joy unless they’re hurting someone. They see attention as a finite resource. The verification was only supposed to mean that your account was in the public interest and you were who you said you were. But that meaning changed. Those without checkmarks began to see the verification as proof of your elitism. You with your checkmark and large follower account stood for all that was holding them back. And for what? Who gave you a checkmark anyway. You didn’t earn it.

What better target, a checkmark. Not a human with feelings or a family and friends who love them. Just a checkmark. That’s all I’d become to anyone who saw that checkmark in their feed—privileged asshole who hadn’t earned it and deserved to be brought down a notch or two.

I never could wrap my mind around 5000, nevermind 100,000 people following me. I knew that number had to include more than a few who followed me only to lie in wait. I’d say something dumb eventually, or something easy enough to misinterpret. That tweet would take off beyond my usual readers and the beatdown would begin. It happened more times than I can count—my greatest beatdowns include saying I’d vote for Bernie if he were the nominee but I thought he was “kind of an asshole,” calling Kobe a rapist, calling Roethlisburger a rapist, calling Depp an abuser, feeding my dying dog ice cream, feeding my living dog cheese, saying fetch is bad, telling people to read a book before judging it, and perhaps most famously, what I said the night before my book came out.

I’d written a book of essays, essentially a memoir, about my life—growing up in a cult, serving in the Air Force during Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell, the hate crime that ended my career, my sexual assault and subsequent abortion, shitty jobs, jail, homelessness, and more than a few failed relationships. It was about learning to use my voice, learning that I had one at all. That book was coming out in the morning. And I was scared shitless.

I was supposed to use twitter to promote my book. It feels gross as hell if you want to know the truth of it. I don’t know if I’m naturally bad at sales or maybe it’s because I grew up selling Jesus posters on street corners to people just trying to get to work, knocking on unsuspecting people’s doors to sell tapes of shitty cult music. It’s not comfortable, to ask someone to buy a thing. But fuck it. I wanted to be a writer. I could swallow my pride and use the platform I’d built.

An easy way to promote the book was to post reviews. A friend of mine, a friend I’d mentioned in the book, had sent me her goodreads review of the book. I went over to goodreads, got a screenshot and posted that to my twitter feed. Then, god help me, I flipped back over to goodreads.

I’d always been told to avoid goodreads. I thought that was because a bad review might hurt my feelings. It wouldn’t. I wasn’t concerned with bad reviews. I was as excited as any new writer is for a ridiculously bad review that I could send my friends and laugh about. Those who matter to me had loved the book. I loved the book. I’d done what I could. I was too busy biting my nails over what the book would do to my life and the lives of those I love to worry about reviews on a website used to keep track of what you’d read. Or that’s what I thought goodreads was.

What goodreads is is a septic slurry of cruelty disguised as activism, and a tool Amazon uses to sell books at a discount and bankrupt a few more bookshops. But the Amazon volunteers known as “goodreads reviewers” employ the site to destroy anyone who walks past their corner of the cafeteria and so much as makes eye contact. But I didn’t go to middle school. Maybe that’s why I was unprepared for what came next.

I saw two people saying they’d loved my book, then arguing over whether 4.5 stars, a completely made up number, should be 4 stars or 5, more made up numbers. And I thought it was the stupidest damn thing, attaching numbers to books, to words and stories. The funny part is, I was thinking, damn. Y’all can really hurt someone with this shit. Not me. But some unknown author depending on reviews to hit the algorithm.

In the spirit of yelling at the stuck window latch when your house is falling down around you, I said “grow up.” I called them self important assholes in the same tone I call my dog an asshole when he wraps his leash around a pole and I spill my coffee. He ignores me and splits the next pole too because he knows I’m not actually mad at him. I just think I’m funny. My usual readers knew I wasn’t mad at anyone. I was just doing what I do, the coping mechanism I turned into a writing career.

I woke up to something like 8,000 one star reviews. Most books don’t get 400 reviews total. That 1.5 rating I now had was never going back up. I thought. My book was never going to recover, I thought. One bad judgement call, a moment of vulnerability, and everything I’d worked for was gone. I thought.

So I made it worse. Not my best quality and not surprising to anyone who’s known me. I used to do the same as a kid. My stepdad, who never did hear a cliché he didn’t love, would tell me this’ll hurt me more than it hurts you. I was the type of kid who said, wanna bet? Lost the bet of course. Occasionally held onto something I confused for self-respect. Sometimes I still get confused.

When I pointed out that this never happens to men, and it doesn’t, I was accused of comparing reviews to sexual assault. After a few thousand people asked me if I thought bad reviews were rape, I said yep. Because fuck you. Truly. Fuck you.

Anyone with a large following has a similar story, the time they caught the attention of the mob. Twitter isn’t a place for nuance, or sarcasm. There’s no room for assuming a generous interpretation of a tweet, not if you want retweets. Outrage is what sells. Entire accounts are set up to feed off outrage, to livestream the fall of Lauren Hough. I was doxxed. I was threatened. I was accused of harassment and doxxing. My name was trending. Tiktoks were made. Youtube explainers quickly followed.

What the individual user sees as a funny joke, a fuck you to an elitist checkmark, the person on the bottom of the pile sees as an endless barrage of hate and vitriol, because it is.

I was sitting alone out in the tiny cottage on Cape Cod I’d rented so my dog could enjoy a few walks on the beach before he died, thinking I was glad I wasn’t in Texas where I could easily pick up a gun to end the pain the only way I knew how. I don’t say that lightly. I wrote an entire book about why I have PTSD, why I have major depression, why my brain offers up one, and only one solution to seeing the word “rape” tweeted at me thousands upon thousands of times. But I couldn’t talk about that. I couldn’t talk about anything anymore. As a wise person told me during the pile-on, the mob moves on when you do. Don’t say anything. It’s all content now.

Shaming has long been a spectator sport in this country. Social media just makes it easier to attend the shaming. And nothing feeds the mob more than the tears of the mobbed. Fight back and you’re unhinged. Show pain and you’re thin-skinned. (Which has always struck me as an absurd insult. Of course I’m thin-skinned. I feel everything and everything hurts. It’s what made me a writer.)

I survived. My book survived. Somehow. Friends and strangers helped promote the book. My agents and my team at Knopf stuck by me, for which I am eternally grateful. And readers found the book anyway and connected to it. The book made the bestseller list. Nowadays, I watch writers openly talk shit about goodreads. It turns out, that just like diners are tired of yelp reviewers burning down a restaurant because they didn’t get a free appetizer, readers are a little tired of the beatdowns.

But the harassment left a mark. A symptom of PSTD is constant watchfulness. You learn to check the corners. You’re not safe until you’ve checked the closets and made sure the door’s locked. You don’t go back to sleep until you know what made that sound. And you don’t wake up in the morning without searching your name, to see if it’s starting up again. When it does, and it always does—those who were part of the mob have developed a taste for your blood—you don’t sleep until it’s over.

I tried to stay. I thought maybe I could still do some good, promote friends, promote gofundmes—an unfortunate need when we’ve turned survival into a popularity contest. I could promote this substack that pays the bills, build my instagram where I post pictures of my dog and see pictures of dogs. (And yeah, instagram is as evil as the rest. But I still have to sell a book.) But what started as “Lauren Hough compared book reviews to rape” is now “Lauren Hough hates trans people.” I didn’t. I don’t. But that doesn’t matter. The truth has never mattered on an app that feeds on outrage.

Twitter taught us that too. Outrage gets views. Outrage gets retweets and likes. Outrage and hate and anger spread and drown out the light. You learn fast that a well-timed dunk on a trending topic will grow your account and with it, your influence. It’s why it’s so tempting to join in a pile-on. For some, for those invested in spreading hate, the pile-on is the goal. Ben Shapiro knows this. So does Matt Walsh. So does Ted Cruz. Every time we quote tweet them with our funny joke, we spread their message of hate.

Creators and artists and writers are scrambling right now. We know Twitter no longer serves a purpose. We’ve watched the platform dry up as casual users leave the site in droves. The new algorithm buries our tweets. The only time anyone notices our feeds is if we step afoul of a roaming mob. So we don’t tell jokes anymore. We don’t talk about anything personal. We barely tweet at all and our accounts just fall further into in the ether. Many of us who write are here on substack now where we can freely write and with any luck, earn something for our work. But without something like Twitter to promote it, we’d have to rely entirely on our readers to promote it for us.

I’m lucky that my readers do. And I’m grateful. But Twitter is also how we found writing jobs. How editors found us. How we made those connections. How we pitched and sold stories. No one knows how we do that now. I’m lucky in that I do have a pretty solid reader base. I know a few editors. I think, I hope, that I can still sell my work. And Twitter no longer seems like a place I’ll be able to make those connections anyway.

But like any addict, I couldn’t stop looking. I knew what twitter had done to my mental health. It’s a humiliating thing to admit, that I’ve sat in the waiting room of the mental health clinic at the VA, desperately waiting to see a doctor, to talk about why I wanted to die, because of fucking twitter. All I had to do was log out. Delete my account. All I had to do was stop. But I couldn’t do it.

Like I said, I’ve been tapering off—tweeting less and watching my views drop. I’ve been trying to develop better habits—don’t check it in the morning, don’t check before bed. Read a book. Go for a walk and leave my phone at home. But I always come back. One more tweet. One more cigarette. One more hit.

I started dating someone who isn’t on twitter. She didn’t know what they say about me over there. It’s not a fun thing to have to explain. But I tried. This is why people hate me. This is what they think I am. Please believe I’m worthy of love anyway. I felt like a basement dweller showing her my piss-stained lair and asking her to stick around. I clean up okay. I open the window sometimes. I go outside. I swear.

I’ve been driving around the country talking to friends and strangers, thinking a lot about what matters. What matters to me is having a voice. What I like about myself is I am a writer. Not that I have (had) a checkmark, not the number of followers I have this week. I wrote a book that I’m proud of, and I get to write another. I want to be proud of that too. But I’m not writing when I’m on twitter. And I no longer think my staying has any value.

It’s never been so clear as it was Friday night, when I couldn’t wait to watch my checkmark disappear. When I got out of bed, to fucking check twitter. To be real damn clear, I could’ve been big spoon. I could’ve stayed in bed next to a real human being who actually likes me. But I got out of bed, to look at a fucking app that causes me nothing but pain. Goddamn.

I decided to not wait around to die. I changed my name to Ted Cruz and tweeted this, and a few more. I didn’t know I’d get banned, not with any certainty. But I knew it was likely. I did it anyway.

I’m a slow learner, but I finally did learn. Yeah, I had friends on twitter. But I wasn’t among friends. I will not longer be part of what separates us. What spreads hate. What’s making us all so lonely and sells itself as the cure. I won’t be a part of it. I won’t be another name attached to hate. A name that a kid somewhere hears and thinks goddamn, it really is everyone. I won’t sell myself for someone else’s gain. I won’t provide the content that sells ads and keeps even one person on a site that at this point only serves white supremacy.

I’d like to think I’ve done some good with my account. But I can no longer lie to myself that keeping it was doing any good at all. I only wanted to be a writer. I likes that about me. I hated what twitter does to me. One addiction at a time I guess. This was the easy one to kill. Maybe I couldn’t see it until I saw my reflection in someone’s eyes—that being a writer is what I like about me, not my follower count.

This is the sort of thing that sounds trite on twitter. I wanted to be a writer so that I could have a voice. But what good is a voice if I don’t stand for something, if I’m too scared to use it.

I’m not on twitter anymore. I don’t know what will happen to my career now. I don’t know what it’ll cost. But I’m not and I won’t be sorry.

This one should be published, Lauren. Also, brava.

You were my favorite on Twitter. Then you wrote a book, which I loved and told other people to read. Then you (and Cate Blanchett) read the audiobook, which I loved and told other people to listen to it. Then I found I could follow you in my mailbox and I get more of you and it beats Twitter. Keep writing. I'll keep reading. I'll keep telling other people to read your work. Also, you pushing back on unsolicited advice has made me a better person. Reminders that opinions or advice doesn't have to be shared is under appreciated. Safe travels. May you find some good laughs, some great dogs, and true friends along the way.