It started as a joke, or something like it—what would happen if I dropped acid and listened to some of the music that got me through those angsty years.

I was already planning to drop acid. It’s the sort of thing you do when you have some acid and you haven’t done it in a while, long enough to have forgotten that it’s exhausting and you really shouldn’t plan to drive the next day. I’d forgotten. So I made a playlist and checked a dark skies app and booked a couple nights at a cabin. But there was a breakup and a replacement acid buddy. And he kept talking about nirvana, the concept, not the band, the gurus and philosophers he’d read. I managed to not tell him to shut the fuck up and come look at the stars and fucking feel it.

I kept listening, adding to the playlist. When I got to my brother’s house for Christmas, I put it on and invited him to add to it. I needed him involved. I told him that. I need you to add to it. I forgot too much. You had the tape player in your room. You had the stars on the ceiling. I didn’t know that song was Elliot Smith until I downloaded it later on Napster.

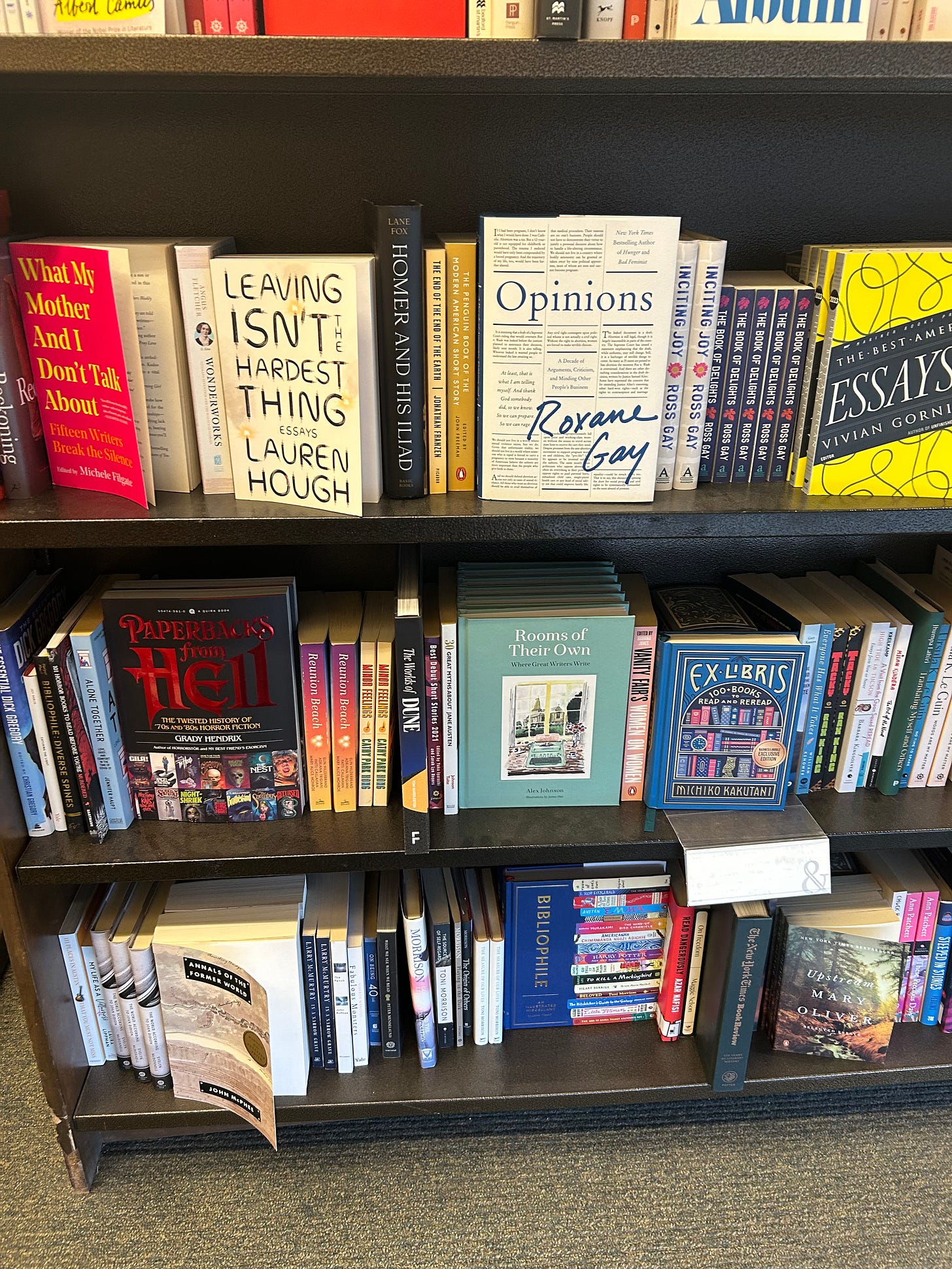

Last night, I was in a hotel room in Amarillo, where I’m from, or sort of from but it’s a long story and I wrote a book about it. I checked, before I even got to the hotel. I pulled over at the Barnes and Noble we were so proud to get back in ‘94. We were like a real city with bookstore and a cafe. I walked in and the store smells a little funny now, everything in Amarillo tends to. But there was my book on the shelf, the reference shelf. Which seems like an odd location except that it’s here, in Amarillo. My book’s called Leaving Isn’t the Hardest Thing. And right around the corner from the Barnes and Noble is the Air Force recruiter where I signed up the day after I graduated high school. So maybe it does belong in the reference section. This time I made back to my van before I started crying. I put the playlist back on and drove down to the hotel

.

Because I was in a hotel, I watched the Grammys and cried when Tracy Chapman sang Fast Car and bawled when Annie Lennox paid tribute to Sinead. But I kept seeing all these people confused. I’m still seeing them today. I wanted to explain. But there’s no way to explain unless you were here, not just that, unless you were here then.

You weren’t here when the only songs we heard on the radio were by artists like Snow and Jodeci and UB40, artists you’ve never heard of and we’ve forgotten. Check the Top 40 from back then. These songs, the songs we talk about now, the songs that make us cry, they never made it all that high on those lists, not enough to get play on the radio in a place like here. Even when Kurt died, he didn’t break the top 10. You wouldn’t know that listening to people like me talk about gen-x online like we were all listening to the same shit. We weren’t. But you weren’t here the year the only song on the radio was Whitney Houston’s cover of I will always love you. And it’s a great song. But it was the only song.

You weren’t here when we had to stay up past midnight to even see a band we loved on MTV. You’re here now, wherever’s here to you. When you ask someone my age if they were into Nirvana, they claim of course they were, loved Nirvana. Same way they were all against the war in Iraq. You don’t understand that we never heard these bands when someone else was around, because no one else was into them.

You can miss that little fact nowadays when you log in and it seems like everyone my age is crying because Tracy Chapman played a song. We forget too. That it wasn’t all of us. It wasn’t even most of us. We were the only ones we knew who listened to any of that and we didn’t talk about it with anyone.

You didn’t want to be too into music back then. The guys thought Metallica ruled and Alan Jackson was alright. You’d drive around with your boyfriend who carried a bat in his truck and you did too because everyone carried some kind of weapon in this town. He’d play an Adam Sandler tape or turn up the Ugly Kid Joe song, but he wasn’t into music. He wasn’t some kind of fag.

You’d get off work at Taco Villa, the one that’s still there on Coulter, and gather with the guys at the back of Rocky’s truck and that Boyz II Men song would be on but no one was listening. They were throwing Red Dog cans at the fence and talking about going over to Cody’s to shoot baskets or Rocky heard there was supposed to be a fight later at Western Plaza where a couple years later, they killed that kid Deneke. Trent said fuck that, let’s go to Maggie’s, the gay bar across the highway, throw beers at some queers.

This was a real conversation. The fence is still there. I drove by today and Mother Mother came on when I pulled up to the drive through where I used to work. So I went around again and picked up a couple burritos and an iced tea. Maggie’s is long gone.

Back then, hearing the plan for the night, you might still be bothered. But you didn’t say shit. You went home instead, you were allowed because you were a girl, and your brother was in his room with the lights off, listening to something you’d never heard before. That wasn’t a thing that happened too often, hearing something you hadn’t heard, something different. There was that one time the college station played a song you hadn’t heard. There was no way to know who or what it was. Couldn’t google a few lines. Couldn’t use an app. You could call the radio station, I guess. But you’d have to pull over and find a payphone. You didn’t hear that song again for years. Didn’t know it was Elliot Smith or that you loved him.

I drove past that house today. Luscious Jackson was playing. My grandma died long ago. But I could see my brother’s window from the street. I assume someone took the little plastic stars off the ceiling.

But that night, imagine it, because this is real, imagine your brother’s listening to something new. You start to talk but he says, “Listen.” And you hear the squeak of the tape rewinding and the clack of the play button. He turns up the volume. You drop your bookbag and sit on the floor and hear the words, the pain that sounds like something inside you, the thing you don’t have the words to express. You’re lying on the floor of your brother’s room and the plastic stars are the only light you see and you imagine a place that’s not here. It’s not easy in a place like this, where you can see forever, not a goddamn thing to break the horizon, strain your eyes looking and there’s nothing fucking there.

We didn’t have the words for much back then. We didn’t know what “toxic masculinity” meant. We didn’t have a word for that time the assistant football coach was teaching the health class and asked, “What does ‘no’ mean?” and all the boys shouted, “Harder.” We knew the queer jokes and the rape jokes and how they talked about you, if you didn’t smile and laugh along with them, if you didn’t think they were funny, if you wore the wrong jeans, the wrong shoes, the wrong haircut.

They tortured my little brother, those guys who weren’t into music. They tortured him because he wasn’t into football. He was into art and music and, had we known the word, a little fastidious about his clothing and his hair. He was too clean. All his friends were girls. The guys called him a queer and a fag and that wasn’t the worst of it.

He couldn’t catch a break at home either. Our stepdad, who once explained too loudly in a booth at a vegas buffet, that Magic Johnson only had AIDS because he took it up the ass, had a lot of opinions about his stepson, who wasn’t into football. Our stepdad was, for a time, so worried about my little brother that he forgot to worry about me. After all, I was safely dating a cowboy. But my little brother, that kid spent too much time on his hair. He was too sensitive. Spent too much time with girls. Our stepdad, who still lives here but I didn’t pay him a visit, he wasn’t saying my little brother was gay. He was saying it could turn out that way, if he wasn’t bullied enough at home and at school and god knows where else.

That night, imagine you’re in a place like here, in a time like then. Imagine you listen to the whole tape with your little brother, A side then B side. You ask while he’s flipping the tape, “Who is this?”

He says, “Nirvana.” That’s all you say all night. In the morning, you drive over to Hastings and buy a tape of your own, and with your next paycheck, another. You don’t know where your brother was even getting these tapes. A girl in his art class. A boy at summer camp. Who knows. That’s how we found bands back then. Tapes passed like a secret. A vow that said, I’m not one of them. I like this shit too.

We were surrounded by them. We forget that now. How lonely it was to have a thought, a feeling. How uncool. Boys didn’t have feelings. They rubbed some dirt in it or shoved someone into the girl’s bathroom. They were allowed two feelings—rage, and occasionally joy, if the joy was about football, or Jesus. The music that no one listened to that played everywhere was about nothing at all. We forget those things because we want to think our generation was different. We forget that they were the same. We were different.

My little brother kept finding music and I never asked him how. He’d give me a Mazzy Star tape and say, “You’ll like this one,” and he’d already have moved on to Nine Inch Nails or the Pixies. We didn’t find them in order because how would we. I’d find magazines about the bands and we’d pool our money for the new Pearl Jam tape and drive around in my car going nowhere at all until we’d heard both sides, twice. And when we got home, our stepdad would tell us he’d heard that singer we liked, and he always got the name a little wrong on purpose, but he’d heard that guy was a queer. He said, and I am not making this up, that Last Dance with Mary Jane was about drugs. Tom Petty wasn’t slipping anything by him with coded lines like, “One last toad to kill the pain.” That meant mushrooms, Lauren.

You didn’t tell people about them, not that anyone asked, these bands we listened to. You heard the jokes either way. How they were a bunch of fags. And another word. Because they wore dresses. And they did, they, plural. Billy and Shannon and Scott and Perry and Trent and Kurt.

The guys before them did too. They wore makeup and feather boas. But those guys were okay because they fucked bitches and dated porn stars and made sure everyone knew. No called those guys those names.

But Trent, Kurt, Billy, Perry, Scott, and Shannon, they wore dresses and makeup and cute little clips in their hair. Because fuck them is why. It was a joke that they, they, the guys who tortured all the boys like my brother would never understand. Guys like my stepdad who told us Kurt ended it because he was a fag and since you’re crying, that’s what killed River too, they wouldn’t get the joke. The joke was for us, the joke was for my brother. The joke was that you would see a guy wearing a dress and you wouldn’t understand and you’d think it meant anything at all. It’s just a fucking dress. But if you didn’t get the joke, you could call them whatever the fuck you wanted. They didn’t care. We forget that too, how many didn’t get the joke. It’s why we think it’s a little strange, when you see Kurt in a dress and decide he must’ve been trans. Do you know that you sound a lot like our stepdad, like the guys who threw beer cans at the queers? Funny how that happened.

It’s funny now too, that those were the charges against my brother—he was into art and music and a little fastidious about his clothing and his hair. He didn’t like football. He was too clean and all his friends were girls. And once, his senior year, he wore a dress to school. It was more than enough to convict him in this town at that time. But this town’s funny about convictions.

They didn’t convict Dustin Camp for killing Brian Deneke in the Western Plaza across from the iHop. My brother stayed at the iHop when the fight broke out and everyone got their weapons out of their cars, the bats and the chains. But in the end, it was a car that killed Deneke, ran over him and dragged him and I’m glad my brother stayed at the iHop because he didn’t want to fight. Plenty of boys did. They killed his friend across the street. But Camp was a good Christian boy who played football. Deneke was a punk who was into art and music.

My brother now lives in a New England town with his wife and his kid. The charges against him are still true. He’s still into into art and music. Still clean. Still spends too much time on his hair. He once wore a dress to school. But that doesn’t mean anything anymore, or it doesn’t mean what it meant here, back then. I wonder now how much that has to do with Kurt Cobain, and the rest of the men who wore dresses, who wrote songs that told us it was okay to be a person who feels things, to be sensitive, to cry when something touches your soul. I wonder if they managed to change how people looked at someone like my brother, or if they changed how he thought a man had to be.

I drove past our old high school when All Apologies came on, and I rolled down the window but I didn’t slow down. I was headed out of town, one more stop, the canyon where I used to drive with my mix tapes scattered on the passenger seat. I like driving away from this town. Maybe I come back here to remember that I did, and I still can. You can still see a thousand miles and still not see a damn thing. But I left. I’ve been a lot places beyond the nothing. I like leaving here. I know there’s something out there.

The playlist, in case you like to feel things:

Here’s another piece I wrote about the music that meant something to me.

A Year of Borrowed Hope

It’s weird that I only remember my first roommate’s name. Or maybe it’s not. That year, 1996, it was a long time ago, and it was a strange year. I have memories like student films, fuzzy and obscure. A driving scene. A car I borrowed from Airman Brightwell or m…

Here’s a piece I wrote about Sinead.

Sinead.

I think it was sometime in the pandemic. I have no access now so who knows. I said something to the effect of all you motherfuckers owe Sinead an apology. And I got a DM from an account saying only two words, “Thank you.” But with a heart instead of a period. I thought it was spam. Like being followed by @keanureeves3391842. Wasn’t her official account.…

God Lauren, I actually have tears streaming down my face. Hard to articulate how some of these songs saved me and how your writing guts me but I’m grateful.

Goddamn you took me back to my shitty little suburban town with the good football team. And finding Nirvana at the little record store. I was a punk kid whose friends were mostly girls, who got the shit beat out of him. I'm still in touch with the friend who gave me a mix tape with the Dead Kennedys and Talking Heads back in '83. We feared 2016 because we remember what the 1980s were like.